There is something cathartic about consistency: a recurrence of style so appealing that it borders on the ritualistic. If one has a circle-shaped block and is tasked to fit it in a circle-shaped hole, don’t turn it into a square. It is futile, even in the face of a perceived ability to be versatile. There’s something to be said for the steadfastness one must have to remain true to the consistency that has made them the greatest director in the history of cinema. It’s comforting to know every turn before you reach them, even in spite of how ritualistic it may feel.

This film starts with a ritual. The landscape differs from Jordan Belfort’s debauchery-filled office at Stratton Oakmont, and the circumstances are graver than those of Colin Sullivan on the streets of Boston, but it’s a ritual all the same. The landscape is 1920s Oklahoma, and the circumstance is an epidemic of greed spreading throughout the Osage Nation. Oil has been found, making the members of the Osage Nation “the richest people, per capita, on earth.” Enter Daniel Plainview: “I drink your milkshake!”

Immediately, you are privileged with a sort of conveyor belt of Scorsese trademarks: a slow-mo sequence of the Osage striking oil, celebrating their good fortune to a Robbie Robertson soundtrack. Freeze frames, shades of Jake La Motta, capture the emotionless faces of the Osage tribe accompanied by their white guardians. Oil has made them rich, but it has also made them targets. Unexplained and uninvestigated murders plague the nation.

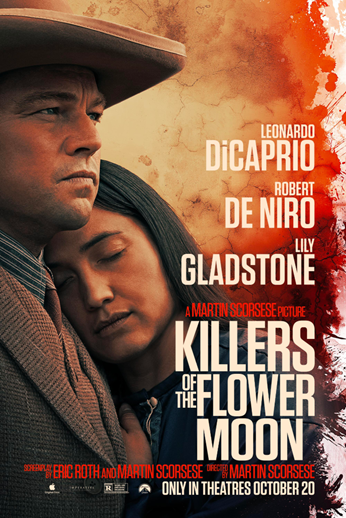

A beautiful transition shows a befuddled and wide-eyed Ernest Burkhardt, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, with his bottom lip tucked in, a stark change in direction in his oeuvre. Enter W. K. (King) Hale, played by Robert De Niro, the uncle to Ernest and a man ferociously resolute in his role as arbiter. “Do you like women? What about red ones?” Their bond is one of fixation, eyes focused on one goal, completely devoid of the ability to conjure emotion. Their relationship is complicated, characterized by power dynamics and manipulation. Advancement is crucial to the cause.

This incapability of emotion is tested, albeit slightly, when Burkhardt meets Mollie, played by Lily Gladstone. Scorsese, not an Osage, chose to tell the story more through the lens of Ernest than of Mollie. As a result, a seemingly compassionless man appears to have compassion in the way he looks and talks about his wife. There was no love, no compassion, but Marty won’t tell you what to think. He’s more nuanced than that.

As the murders increase, an investigation becomes inevitable. Tom White, played by Jesse Plemons, is sent on behalf of the Bureau of Investigation. Unfamiliar terrain, a distrusting community, and powerful, subliminal forces make it difficult for White and his agents. The desire to uncover the truth is met head-on by the determination to preserve and protect the fabricated legacy built from Osage wealth.

Marty captures the macabre in a way that shockingly reveals what we already know. The history of white men going to inconceivable lengths to exploit those deemed beneath them is both long and abundant. It might not have been a good idea to give Ernest Burkhardt a conscience, but one could argue that this only magnifies the severity of his crimes in the eyes of the viewer. He couldn’t possibly do these things, right? Of course, he can.

The film is incredibly stimulating, in part due to the range of emotions triggered. It’s dreadfully sad at times and insanely funny at others. Scorsese and long-time editor Thelma Schoonmaker navigate these emotions perfectly with short sequences and what seems to be an insane number of edits. They take us from a screaming family member at the sight of yet another dead body to Burkhardt hilariously absorbing a speech about how he, the white man, is the true problem. The core of the cast is utilized perfectly as sparring partners to drive the story forward.

De Niro uses his off-screen gravitas to channel the characteristics of a master manipulator, exuding both charm and menace. It’s a masterclass in duality. On the surface, he’s a patriarchal figure, seemingly looking out for the best interests of his family and the Osage people. Lurking beneath the facade is a man driven by an insatiable appetite for greed and ambition. He effectively captures the essence of a man who is both a product and perpetuator of his time. It could very well be the best performance of his career.

Gladstone’s ability to convey overpowering emotions with subtle expressions brings to life the complexities of an Osage woman navigating both personal and societal challenges. Her perspective is deeply human, serving as a window to the joys and sorrows of the Osage people. Her resilience and determination create a palpable sense of relatability. Her performance is central to the success of the film, grounding its dramatic events in genuine human experience. She’s fantastic.

DiCaprio is able to vacillate between moments of tenderness, particularly with Mollie, and periods of palpable tension, showcasing the nuances of a man caught in the crossfire of morality and greed. He moves back and forth from moments of vulnerability to those of concealed malice, executing this with near perfection.

Scorsese’s signature touch is evident in the film’s meticulous attention to detail. Be it Jack Flick’s production design or Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography, the beautiful details in the film, juxtaposed with the haunting reality, are both tense and tangible. Every frame, every edit seems to breathe life into the pages of David Grann’s novel. His direction of such morally void characters is deft. His pacing of the suspenseful and intense subject matter is masterful.

Guilt, redemption, and the dual nature of humanity, capable of both immense evil and deep-seated goodness. These hallmarks of Scorsese’s works have been honed over time into piercing cinematic arrows that target the very heart of viewer understanding. He never shies away from the truth, no matter how raw or uncomfortable it might be. Marty’s position at the pinnacle of the craft remains unchanged; this film simply reaffirms it.

🐘🐘🐘🐘.5

Ranking

I rank all of my movies out of 5 🐘, because I love movies and I love elephants.